Dancemaker, educator, and author Stacey Allen says she carries a message in her work.

“Especially in this moment, where erasure is real and showing up everywhere, particularly in literature, we have to give our children stories that are empowering and rooted in truth,” she said.

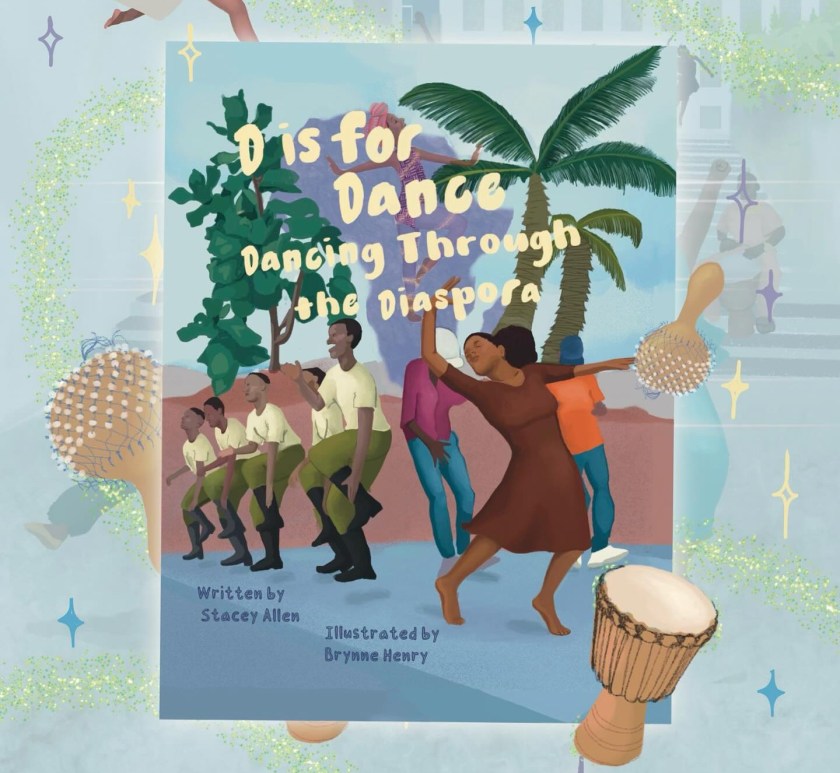

Allen, Founder and Artistic Director of Nia’s Daughters Movement Collective, has written her second children’s book, D is for Dance: Dancing Through the Diaspora, released on Juneteenth. She will present two free, interactive storytimes for the public: Monday, July 28, 4pm at Stimley-Blue Ridge Library in Missouri City and Saturday, August 2, 1pm at Kindred Stories.

Illustrated by Houston artist Brynne Henry, D is for Dance celebrates the movement, history, and legacy of the African Diaspora—using each letter to tell stories about groundbreaking dancers, iconic dance styles, and cultural traditions.

This marks Allen’s second collaboration with Henry. Their first book together was A Little Optimism Goes a Long Way—a story about a young girl who discovers her joy of dancing, inspired by legendary dancer Katherine Dunham—which earned the 2024 Children’s Publication Award from the National Association of Multicultural Education.

“When I was teaching full time in schools, I needed more resources on African American Dance History—so I made them,” Allen shared in a social media post. “Both of my books were born out my commitment to fill that gap.”

That gap has been documented by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), which has been surveying diversity in children’s literature annually since 1994. Of the 3,619 books for children and teens received by the CCBC that were published in 2024, 13% were by Black/African authors/illustrators and 16% were about Black/African characters, settings, or topics. Those percentages have been steadily increasing since 2019, when only 5.5% children’s book were by Black/African creators and 11.8% contained Black/African content.

Allen’s message of empowerment, inclusion, and cultural identity reflects efforts toward more diverse stories for children in recent years. Overall diversity in children’s literature is at an all-time high, according to the CCBC, which reported that in 2024, for the first time, more than half (51%) of the books they surveyed contained significant BIPOC characters, settings, or topics.

Houston Arts Journal reached out to Stacey Allen for the following interview:

Houston Arts Journal: Tell us a little about yourself as an artist and as a Houstonian.

Stacey Allen: I’m always thinking about how I want to define myself. Sometimes I use the term “multidisciplinary artist,” and other times I say “dance artist and educator,” because that’s where my practice mostly lives. But I really like to think of myself as a storyteller who works through multiple mediums, with a focus on telling the stories of Black women and girls.

My passion for education is what really fueled my desire to write these books. As a former public school teacher, I was often searching for resources to teach my students about African American dance history. That was the genesis of these two book projects: A Little Optimism Goes a Long Way, and now, D is for Dance: Dancing Through the Diaspora.

I grew up in the Houston area—Missouri City, to be exact. “Mo City,” as we affectionately call it. For me, growing up in the late ’90s and early 2000s, this was my Black Mecca. I was surrounded by working- and middle-class Black families. We went to church not far from home, and before I started public school, I went to a private Christian school that emphasized African American history. I later attended two public schools named after Black leaders—Edgar Glover Elementary and Thurgood Marshall High School, both in Fort Bend ISD.

That environment really nurtured my love for culture. Of course, my parents and family poured into me too, but I never saw my cultural upbringing as something deficient. I grew up in a version of Houston that was diverse, vibrant, and deeply multicultural. So when people talk about Houston becoming known as a Black city, that resonates with me, because Missouri City already felt like that.

HAJ: How did you discover your love of dance?

SA: As a young girl, I grew up dancing in church. You’ll see in the book that “W is for Worship Dance,” because my church experience was central. We did praise dance at church, and I also took classes at a local dance studio not far from where I grew up. Then in high school, I joined the dance team.

That was really the beginning of my love for dance. And as I got older and met other people, I realized that story wasn’t unique—so many of us grew up dancing in church, maybe taking a few classes at a neighborhood studio, and then joining a school dance team. At my high school, which was predominantly African American, we performed majorette-style routines. That’s why “M is for Majorette” shows up in the book—it’s a direct reflection of how I came up in Houston.

HAJ: Why did you want to write this book, and what was the initial spark that inspired it?

SA: I’ve been able to experience so much through dance—it’s shown me how the world is so big and so small at the same time. Through dance, I’ve traveled, met people from all over, and been part of something bigger than myself. I wanted young readers to have that experience too.

I want them to see that movement connects us all. It connects us to each other, to our ancestors, and to our future.

HAJ: The book’s title is D is for Dance, but inside, the letter D stands for Dunham. Can you tell us a little about Katherine Dunham and her influence on you as an artist?

SA: Katherine Dunham—oh my goodness. This isn’t a spoiler alert, but if you haven’t read my first book, A Little Optimism Goes a Long Way, I highly recommend it. That book centers a young girl who looks up to Katherine Dunham.

To me, she’s the epitome of dance and activism. She was an anthropologist who studied dance from all over the world—especially Afro-Caribbean traditions—and brought those styles to the stage. I’ve read that Alvin Ailey saw Katherine Dunham’s company and was inspired to pursue dance. So when you think about the level of impact she had on movement and cultural studies, it’s just beyond legendary.

And for a Black woman to be doing that kind of work in her time? That’s something people need to know. So even though she’s a central figure in my first book, I wanted to be sure she had a place in this one too.

HAJ: I love that Houston makes an appearance in the book under “H is for Hip Hop” and “Z is for Zydeco.” What other letters were particularly fun or deeply personal for you to pair with stories?

SA: Honestly, I had fun with every letter. I know that sounds like hyperbole, but it took a long time to figure out which ones to include. For example, for the letter “S,” I went back and forth—should it be Second Line? Samba? Salsa? So many Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latinx dance forms could have made the list. There were several letters I had multiple ideas for, and then a few that were honestly harder to fill. But where I landed, I feel really good about.

And yes—look, I know hip hop started in New York, but I also know “the South got something to say” (quote from Andre 3000) and has contributed so much to the culture. There was no way I was going to make a book about the African diaspora and not include the SouthSide. That was just never going to happen.

Same with Zydeco—what is more Texas-Louisiana than that? “Z is for Zydeco” had to be in there.

I also really wanted the book to reflect my roots in what I call the Afro Gulf Coast—places across the South where there are large concentrations of Black people because of the legacy of chattel slavery, and where cultural innovation continues today. We’ve made so much out of very little, and that creativity deserves to be centered.

HAJ: Place, family, and motherhood seem important in your work as a choreographer. I see these themes in your piece The Fairy Tale Project and in this book. How do they guide and motivate you as an artist?

SA: Place is how we understand the world and ourselves in it. I can’t talk about who I am without talking about where I come from.

I’m a descendant of a freedom colony “Eleven Hundred” in East Texas. My mom’s side of the family came from there, and my grandparents later moved to Oak Cliff. My dad’s side left rural Mississippi, went up to Niagara Falls, and eventually settled in Buffalo—in the Fruit Belt, an African American neighborhood. My parents raised us in Missouri City, a rising Black suburb at the time.

So when I talk about placemaking, I’m talking about all of that. That’s also why I will always reference the groundbreaking work Texas Freedom Colonies Project and The Outsider Preservation Initiative led by Dr. Andrea Roberts. Her work shows there were over 500 places in Texas founded by Black people post-emancipation. That history of land ownership, community building, and cultural preservation is powerful—and it’s relevant now, especially as more people consider moving back to the South or starting to homestead.

Motherhood has made me even more focused on legacy. I was an educator before I was a mother, but becoming a parent deepened that passion. I’m not one of those artists who says, “You just take what you take from the work.” No—I have a message. Especially in this moment, where erasure is real and showing up everywhere, particularly in literature, we have to give our children stories that are empowering and rooted in truth.

Houston illustrator, mixed-media artist, and educator Brynne Henry / courtesy of the artist

HAJ: This is your second collaboration with artist Brynne Henry. What draws you to her art, and can you share a little about your process together?

SA: Brynne and I were connected by our families—so that’s how I first became familiar with her work. And honestly, her work is just beautiful. I hope readers take time with both books—D is for Dance: Dancing Through the Diaspora and A Little Optimism Goes a Long Way—and really absorb the care and detail in her illustrations.

Our process this time was even more involved. I finished the first draft of D is for Dance while I was in Senegal, so I had a lot of source material. The tree on the cover, for example, comes directly from a photo I took during that trip and holds symbolic meaning. I sent Brynne tons of visual references—because we’re both educators, and we wanted readers to see not just dance history, but also visual culture and material culture from Africa and the African diaspora throughout the book.

HAJ: What are your hopes for this book?

SA: I hope people see themselves in this book. I want readers—especially children—to remember that everybody can dance. Dance is for everyone. It’s a gift we should all be able to experience.

I also hope people understand how movement has carried us—not just in the physical sense, but in the cultural and spiritual sense. Movement connects generations. It’s tied to identity, resistance, joy, and healing. And I hope people see that movement can be the beginning of other movements—social, political, creative.

Finally, I hope this book becomes an educational resource. A tool that opens up new ideas, introduces new histories, and brings young readers into new worlds.

Glad to see you connect with Stacey. I think she’s amazing and so clear and focused on her purpose. I’ve interviewed her a couple of times and it’s always an inspiring conversation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed your article about the book in Dance Source Houston!

LikeLike